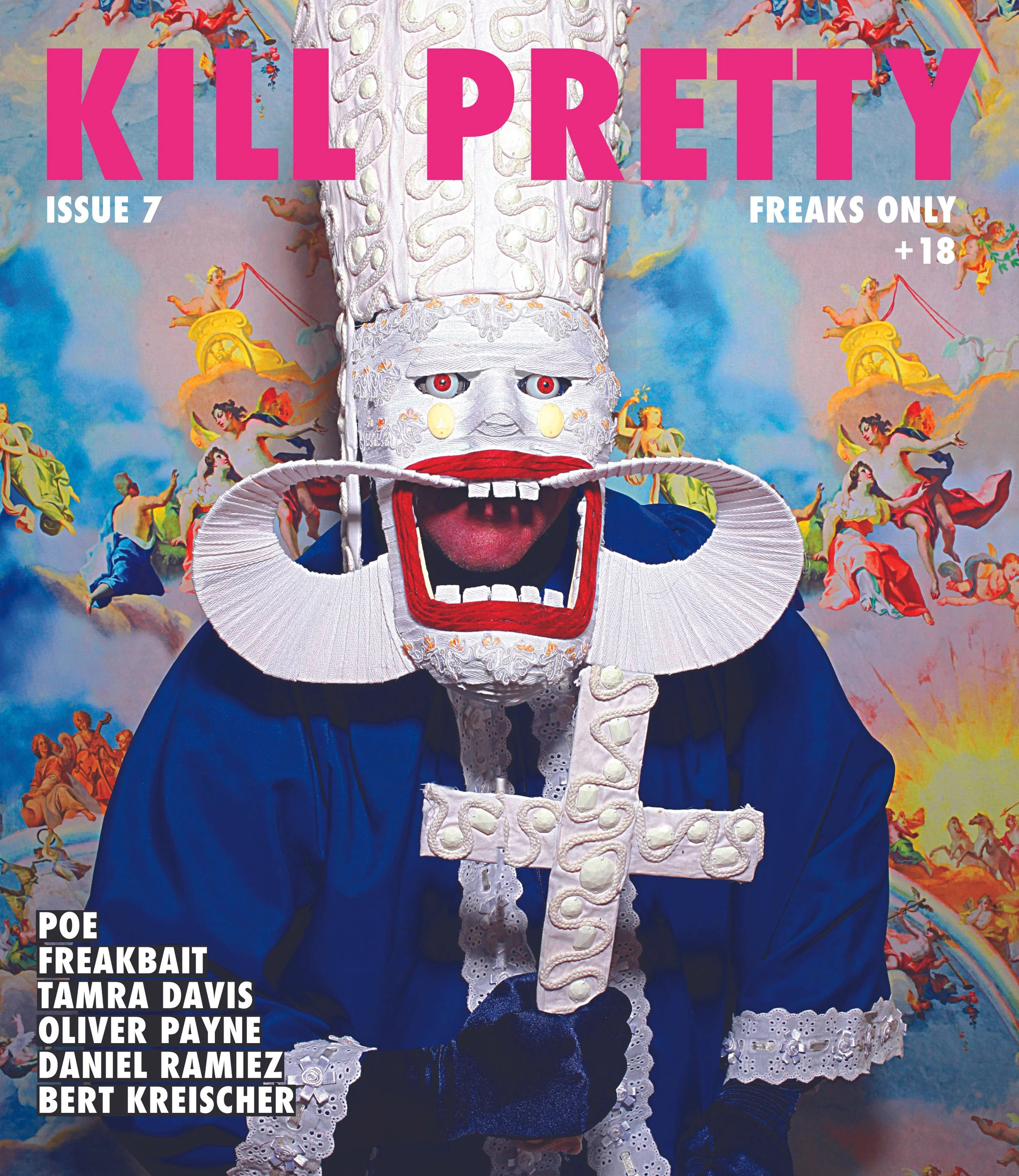

Thoughts on Re-Animator, Lovecraft, and Teenage Obsession

/As a latchkey kid coming of age in an incredibly unstable household in the early 90s I gravitated toward the spooky, the strange, and the macabre. Lunch time discussion with my twisted chums rarely ascended above who had seen the goriest film or read the creepiest story over the weekend. Andrew Guthrie, all red hair and freckles, tended to lord over the conversation with spot on retellings of Hellraiser 2 and Stephen King’s “Tommy Knockers.” Soon, 6th grade turned to 7th and Andrew moved away, leaving me with a hole of horror to fill. I quickly went through a Poe phase, got bored and found a guy named HP Lovecraft. The story went that he lived with his mom, didn’t have a job, and rarely left the house - I could identify. Lovecraft seemed to be born to die. He was a lifelong recluse who remained commercially unpublished until the age of 31. When his stories did finally see the light of day, his attitude towards critics was prickly at best. Those facts lead me to believe that Lovecraft would have hated my favorite offshoot of his legacy.

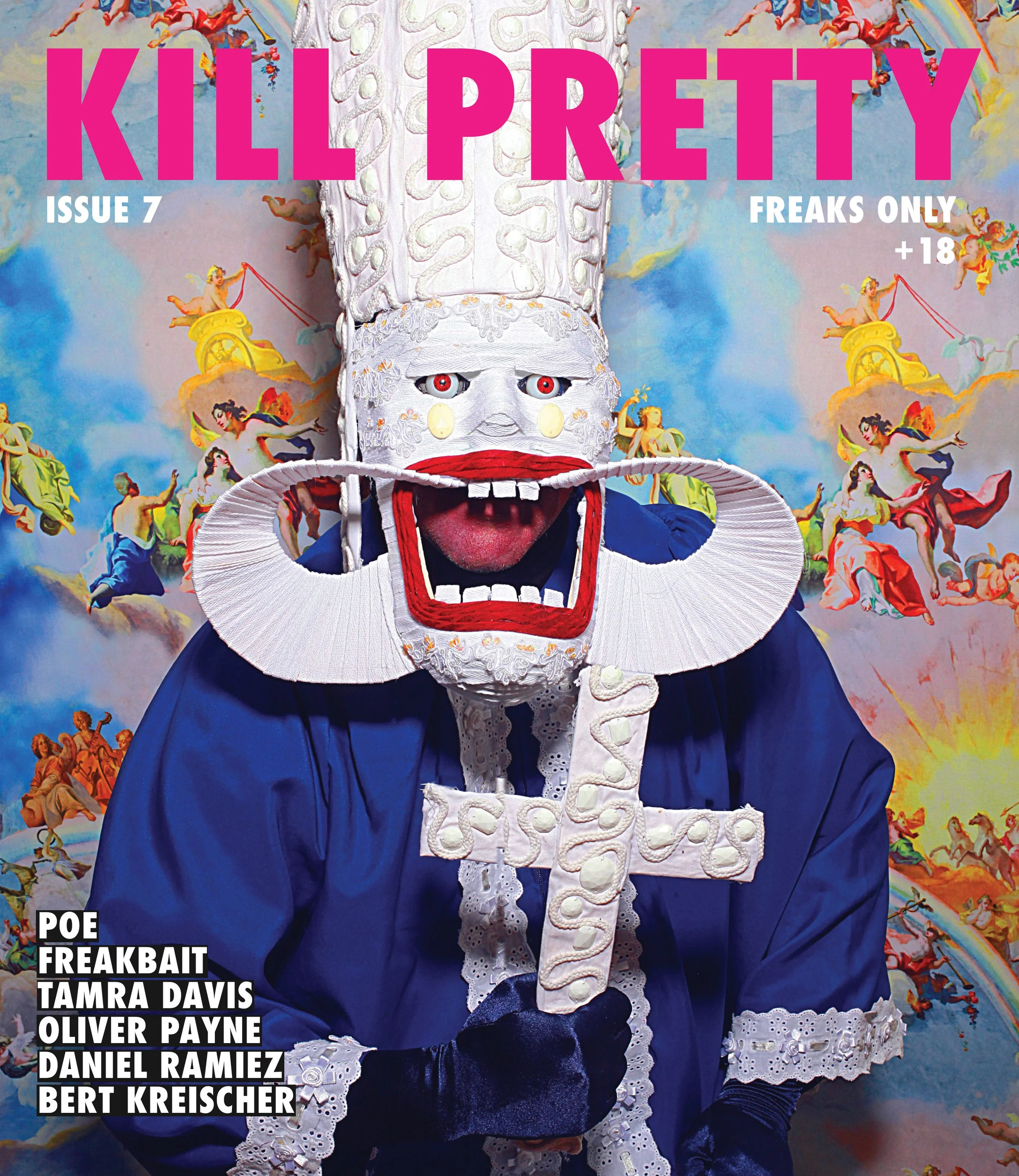

Lovecraft, happy as a clam.

Re-Animator, the 1985 cult classic based on his story “Herbert West – Reanimator.” Lovecraft never gained any real recognition for his work while he was alive and he never lived to see any of the 26 film adaptations of his work; even if he had, Lovecraft was notoriously shy and the chances of the author leaving his home to attend a screening of The Dunwich Horror (let alone the blood soaked Re-Animator) are slim to none.

At 16, Re-Animator was exactly the kind of film that I gravitated towards. A shut in of sorts, I left my windowless room to attend high school and play punk shows in rooms full of people that I was sure hated me. Growing up in a small town gripped by a thick tangle of Southern Baptists and Friday night football (in the fall you were unsure of which was religion and which was sport) all you looked for was an escape. First there was punk rock, or what I thought was punk, I didn’t have the Internet until 2004(!) so it took a few years to find out that I had been doing it all wrong. From there the road broke out in myriad paths: drugs, alcohol, regular small town traps. I gravitated toward the horror section of Video Connection, a small video rental store on the brink of bankruptcy that offered a glimpse of forbidden knowledge via VHS covers that told me to kiss my nerves goodbye, and promised to tear my soul apart. Along with the Evil Dead trilogy, Dead Alive, and pretty much any other movie with “dead” in the title, Re-Animator became a staple in my solo late-night movie marathons. Despite the brutality, gratuitous nudity, and slapstick carnage, the film transcends typical b-movie tropes by embracing them. Owing as much of a debt to Cannibal Holocaust as to Mel Brooks, the film takes Lovecraft’s brooding tale of science gone wrong and casts its leads as if it were a Marx Brothers film. The film is an hour and a half of pure gratification.

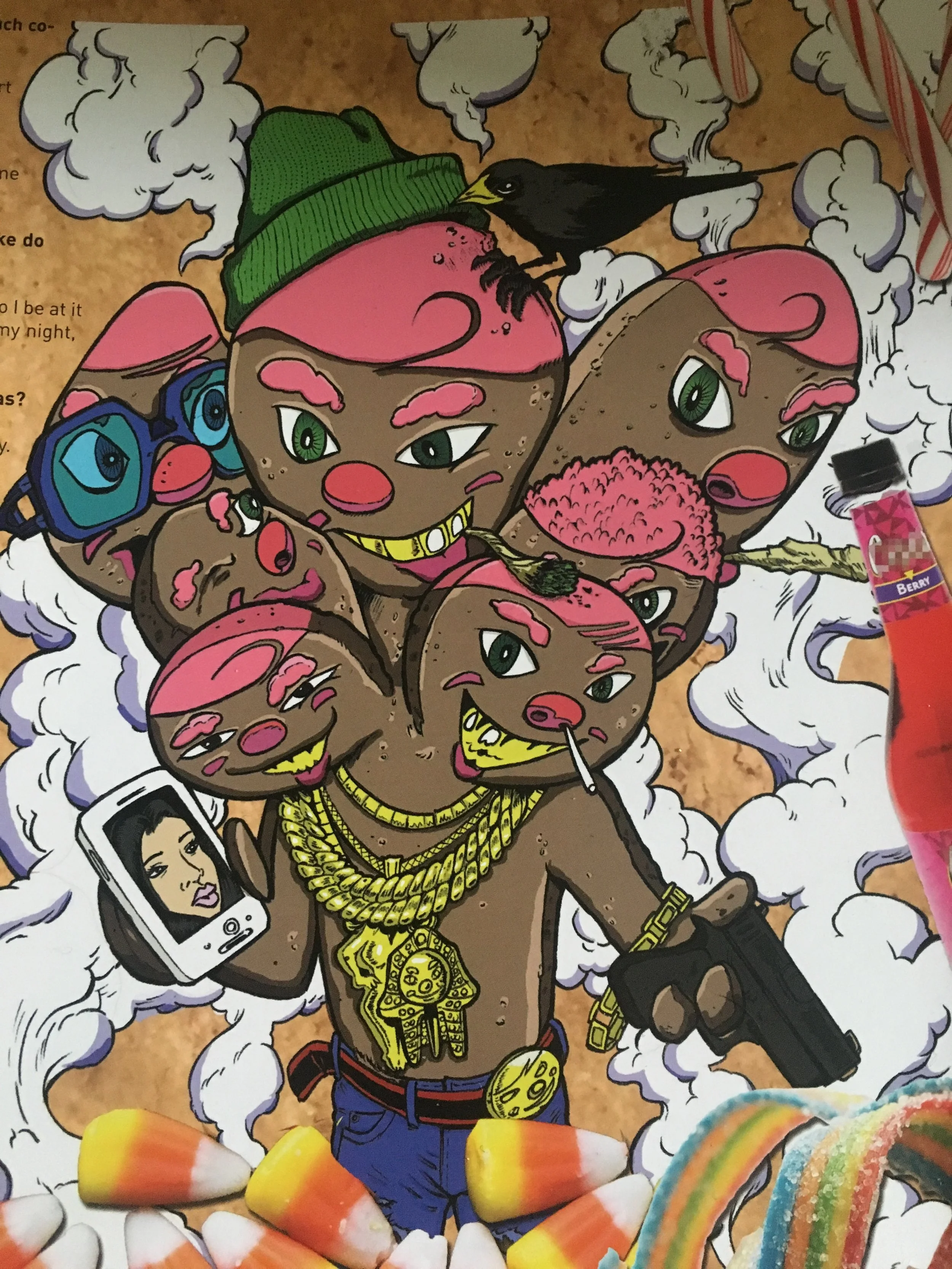

art by Tomas Brewer

If you haven’t been indoctrinated into the world of Re-Animator allow me to give you the basics:

The perceived antagonist, Herbert West, is a young medical student just returned from Switzerland where he developed an obsession for raising the dead. The ghoulish Dr. Hill, who has his own plans for West’s re-animating serum, quickly usurps West’s creepy bad guy role and the film takes a turn for the absurd.

Setting aside perverted decapitated bodies and cat killers, the true enemy in Re-Animator (both the 1985 film and Lovecraft’s original story) is science, and what men do with the knowledge that was at first applied with good intentions. Similar to the hero (for lack of a better word) of Mary Shelley’s “Frankenstein; or, the Modern Prometheus,” Herbert West seeks a way to extend life indefinitely. The underlying fear in all three examples is that everyone we love is going to die and there’s nothing anyone can do about it. Once something is gone, the physical form is gone forever and to bring that thing back (whether it’s a cat or a loving father) is to bring back an entity that has been changed. Ironically, the only character that can see this has already faced the consequences of re-animating and chooses to use something that was originally intended to save, or maybe extend life indefinitely, to control the ones he loves.

more delicious art by Tomas Brewer

On the surface, Re-Animator is a fable of the risks of the modern scientific era that has played throughout literature in every generation. Much like West’s inability to turn back once he’s seen past the curtain to what’s possible with the power of science, I’m unable to watch the film with the set of eyes that I once had. It’s possible that I picked up the underlying themes of the film as a teen, if you asked me I would probably say “I got it,” but when I watched Re-Animator I wasn’t trying to discern the subtleties of Stuart Gordon’s low budget masterpiece- I was trying to spend 86 minutes ignoring my raging hormones and having fun. When I watch Re-Animator now, instead of seeing Dr. Hill’s decapitated body move independently of his severed head, I see a special effects team working at the peak of their abilities and rising above the film’s meager budget.

The more thought that I put into Re-Animator and Lovecraft, the more I believe that the film’s central theme isn’t the rejection of technology, but the rejection of growing old and the knowledge that comes with age.

I’d like to believe Lovecraft would have been fine with the loose adaptation of his work, probably because I have such an affinity for the film. He couldn’t have ignored the Gordon’s slavishly faithful attention to the themes of his work but he probably still would have been put off by the violence. If I’m being completely honest with myself, I doubt he would have sat through the entire film if he even left home at all.